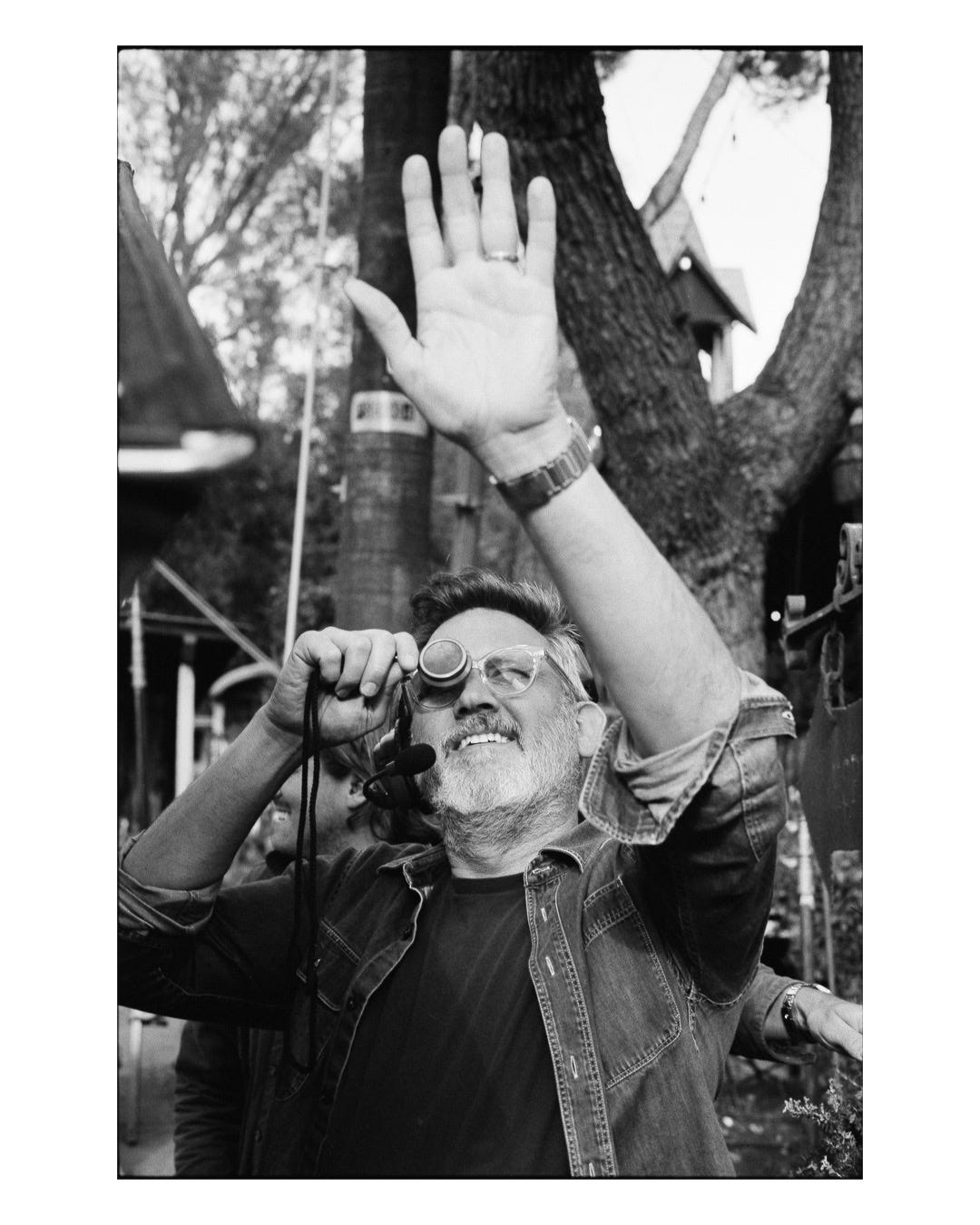

Q&A with Doug Chamberlain

I sat down with a cinematographer who's shot on a variety of high-profile commercial and narrative projects, including the Disney+ Marvel TV show "She-Hulk: Attorney at Law."

One of my first steady gigs after I moved to Los Angeles was a stint as a marketing coordinator at a camera rental house. The experience gave me a deep well of respect for cinematographers and camera operators– cameras on a professional, cinematic level are notoriously complicated contraptions, to say nothing of the knowledge of light, focus, aperture, and focal length required to make sure what you’re shooting looks any good. So it was a delight to interview Doug Chamberlain, a director of photography (DP) who has worked on films, television shows, and commercials across the country and across the world. We spoke about how he got his start, how he prepares for a shoot, and what role his faith plays in his work.

Tell me about what you do – how did you get into cinematography?

My interest in photography really started when I was a middle schooler growing up in Texas. My friend Eric Swenson’s father was a professional photographer, and he was the first one that introduced me to photography. And all through high school, that was my interest. It was still photography – I shot for the school newspaper and yearbook and stuff like that. But Eric, he had a love for cinema and going to the movies. So it really started there. And Eric was really smart on the technical side, so I learned a lot about the technical side of photography. And so when my interests grew even further by going to school and studying filmmaking, I already had this knowledge of photography and I brought that to the game. And I thought, okay, this is something that I can contribute to filmmaking because I had this background of photography.

So you went to school and studied filmmaking at BYU. And then you worked on Napoleon Dynamite. Tell me a little bit about that. What was that like?

I had an amazing experience at BYU – they have so many resources and a lot of facilities to help young filmmakers. They have those big stages there, they have a backlot and they've got rooms full of props and lights and cameras. They really operate at a pretty high level when it comes to filmmaking. Of course, I met Jared and Jerusha [Hess] and Aaron Ruell and Jon Heder and all those guys; they'd worked on some of my school projects, and I had helped on their projects. And so really, coming back and working on Napoleon Dynamite was about helping friends make their movie. And, to be honest, even though rates were low it was still a job working in the film industry, and it felt pretty good at that time. I had graduated from AFI in 2003, and I was shooting a documentary during the US buildup and invasion of Iraq. I was embedded with the Marines, and so I was off doing that. And right on the heels of coming home from Kuwait, I found myself in Preston, Idaho, starting production on Napoleon Dynamite.

Watching Jared work, he was so young at the time and yet clearly is so funny. And that's sort of what the experience was like sitting and working with Jared: he's a really funny guy and he's a very funny storyteller and he also has a lot of heart and cares a lot about people. I think you see all of that in his movies. We had no idea it was going to be as big of a success as it was. We just knew it was funny.

Walk me through those next steps in your career. Where did you go from there?

It was after Napoleon Dynamite that Aaron Ruell and I went and made two short films together. One of them was called Mary, and then the other one was called Everything's Gone Green. We made those, and they both got into Sundance the following year. And from there, Aaron got picked up by this guy named Preston Lee, who was running a company called Area 51 at the time. He really loved Aaron's work, picked him up to do commercials, and we immediately started shooting commercials. And it was incredible. I didn't realize that I was entering into the commercial world at such an elevated level. We were consistently working, and the work was consistently getting recognized. And a lot of that credit really goes to the sensibility of Aaron. He's a great director. He's got a really keen eye for art direction, amazing at casting, and he's funny. And that really launched me into my commercial career, and it’s been such a great blessing to be able to get into that area of work. It's been the majority of what I've done for my career.

Do you have a process as a cinematographer? Like when you get on set, is there a way that you get into the headspace of the movie?

Boy, that's a big question. I think the key when you're working on movies is to be able to get into the head of the director and to get on the same page with the director. You want to be able to understand their vision so that you can support that. You really want to let the project dictate what it wants and then kind of be subservient to that. If I find myself saying, “I want to do this because it looks cool,” or “I saw someone do this one time” – if I ever catch myself doing that, I slap my own hand. Because you want to be true to the project. I feel like it's my job to take the creativity that is coming from the director and coming from the writers – taking that and helping that to be realized on the screen, and employ all the creative tools that I have at my disposal to make that come alive. And then to be able to add my own little take and flair in my own little way to push it forward. I'm usually looking at it from the perspective of the visual tools that we have available to us.

I'm always trying to look at it from this perspective of contrasts. Contrast and affinity. Things that are different versus things that are the same, over and over again. It could be flat space, deep space, high angle low angle, it could be a particular set of lenses. You can shoot everything on a 35mm and then progress towards an 85mm. And using all of those things, you can create a story, you can create narratives using visual tools. It's about building progressions. And maybe the viewer might not realize that's what's happening, but subliminally, it is affecting the way they're receiving the story. Sometimes it's just felt.

Maybe you don't recognize that you're backed up and you're over somebody's shoulder for a scene. And then when you want to emphasize something, you actually go into a tighter shot and then suddenly it's a clean single. That affects [the viewer], and you may not even recognize that there was a difference between those two shots, but it's one of those visual tools that can emphasize an emotion. The difference between a static shot and a shot that's gently pushing in, we all know that difference, and it affects us emotionally. There's a lot of visual tools that we have at our disposal. And so I'm trying to just capture that, as I read the script and get into it, to find opportunities to speak to what we're making using visual tools.

The thing I love to do when I'm working with a director is just to sit down and read the script with them, and then try and understand “Why is this scene?” Like, why is this scene in the movie? And what are the things that we've got to get right in the scene? What are the things that you can't miss? And sometimes it's simple as, “This is a scene where the gun is introduced and we know that something dangerous is afoot.” Okay, well, do we need to make sure that we see that and do we shoot that in a close-up and be really obvious about it? Do we show it in a wider shot? How much attention do we pay? Who knows about the gun? Does the character know about it or do they not know about it? Or are we just introducing it? Is it the camera that’s the only one that knows, you know what I mean? So you kind of work from these moments and things that you want to get right and and the reasons to have the scene there. It tells the story visually. You're just trying to tell a story.

What's your favorite camera to work with? Do you have a lens of choice that you gravitate towards?

I think that's the thing that grows and changes over time, you know? I think when I was shooting film, I was always on Panavision and shot the Primos a lot, but have shot all kinds of lenses over Panavision. And then recently I've been on the Sony VENICE, so that's been my camera of choice. It does everything I want it to do, and I like the look that comes out of it – it's a great piece of equipment. But the lenses we change out depending on what the project kind of calls for. I do have particular lenses that I love and I think are wonderful. I like shooting on Primes and most of the film projects that I've done, when I can, I push for anamorphic. I have an affinity towards anamorphic lenses, I love the characteristics of them. It says cinema to me. It feels like you're shooting for a bigger screen and I like that.

I'm curious in what ways has your faith influenced the type of work you do?

One of the things that's great about the church and about my faith is that we learn through symbolism... And so if we only see that and learn from it, it can really have an effect on you.

So the example that I've been thinking about the most lately is this idea of going back to Genesis, going back to the very beginning. “From dust thou art, and to dust thou shalt return.” Very simple idea, right? But what is life? Life is when you take the dust particles of the earth, right? And they all come together and they all work for one purpose. So they're alive because they all have a singular purpose. And you can look at it and say, look, the hand can't do the job of the foot. Right? The heart can't do the job of the hand, right? And the head can't do the job of the heart. They're all separate, and they all have their different roles. But when they work together and they give themselves over to the one, then life is created. And if you lose a hand, you would say that hand is dead. So death is separation. So as those particles of dust go back to the earth, right, then they're simply separating from each other, and they are no longer working together.

So you can apply that to just about anything. You can apply that to a film set. Like, I have a tendency to get frustrated with maybe a certain department or another. And the quickest way to create death on the project is to be contentious with them. And then the second quickest way is to go and complain about them behind their back and gossip about them, right? So I'm creating death by creating this contention, separation, among the group.

And so the proper thing to do is approach it in a way that creates life here. Let's create good relationships. If some department is struggling, what can I do to help them? How can I truly be supportive and create a oneness with them? And that's been a really helpful thing. I think there's a lot of symbolism that you can take from the world of faith and you can apply it very practically, not just in the film world. You can apply this in any business or anything where people are trying to work together. There's a lot of things to learn from the scriptures.

Love all the different perspectives you are able to get. Cinematography is kind of a mystery to me in terms of the art form, so this was really interesting!

Informative and insightful. Saints & Cinephiles is great.